Back to Related Links  A TASTE OF ITALIAN WINE CULTURE:

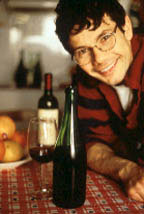

A TASTE OF ITALIAN WINE CULTURE: Wine bottling at home in Piedmont from PASTA Magazine (May 2002) I'm with a pack of American cyclists in the heart of northern Italy's wine country, struggling up and soaring down the formidable hills that are everywhere pinstriped with vineyards. As we pedal past acres of Cortese grapes which produce the white wine called Gavi di Gavi, our Piedmontese guide, Claudio Bisio, continues his impromptu lecture. This 39-year-old Italian who grew up trampling grapes underfoot has proven to be an informative wine guide, so we listen attentively. "This is usually a still wine, but it can be made fizzy if they wait to bottle it until Good Friday, when the moon is full." Suddenly I feel like a time traveler, catapulted back to the Old World, when powdered stag horns served as medicine and astronomy was a noble science. Being a modern-day American, I'm used to discussions about winemaking revolving about soil analysis, fermentation technology, phenolics, and oxidation. The notion of taking the moon as a guide tickles my fancy. Is he kidding? "No one knows why, but it's true," Claudio replies, adding simply, "It's like people being influenced by the weather." Claudio's words reverberate several months later when I notice an instructional flyer in a Piedmont wine shop that spells out the optimal times to bottle your own wine. The schedule is based entirely on the lunar cycle. Clearly, Italians have a different relationship to wine. Rather than being dominated by technology and terminology, it's homey and familiar - the result of growing up with a vineyard in your backyard alongside the vegetable garden, and having a wine glass at your plate by the time you're age five, feet barely brushing the floor. We may know more about wines from different parts of the globe than the average Italian (who retains a fervent regionalism in this regard), but we'll never be as relaxed with our knowledge. That's the allure of Mediterranean wine cultures, and it's precisely the lesson I wanted to absorb. So when Claudio invited me to help select and bottle his year's supply of table wine, I jumped at the chance. A few days after Easter, we're heading north towards a rolling mountain range known as the Langhe. This is Big Wine country - land of bright and sassy Dolcetto, rustic Barbera, and imperial Barolo. I'm delighted that the custom of buying wine straight from the vineyard is still current. "It's pretty common, if you love wine," says Claudio at the wheel of his three-cylinder car. As we putter past ancient hilltowns and vineyards reawakening from winter, he tells me that it was only 20 years ago or so that many producers started selling wine by the bottle. Before that, "people had the time, space, and energy to bottle it themselves" and carted demijohns, much like the 20-liter containers rattling in the back of his car, to the vineyards, where they could sample the wine straight from the barrels and select their supply for the year. "Wine was something to drink every day," he says. "You didn't drink water, you drank wine. So everybody bought big containers of wine, put it in bottles, and basta." Busy lifestyles have changed consumer demand. What's more, as the Italian wine industry has professionalized over the past few decades, producers have had little trouble selling their more profitable bottled product. So today it's no longer that easy to walk into any vineyard and buy in bulk. In classic Italian style, you need to know someone. As Claudio explains, "The producer might just have a little quantity. He'll keep that wine for people who say, ŒI'm a friend of so-and-so's. He sent me here.' It's a magic word: ŒI'm a friend of...' " Having brought dozens of American tourists to the Cantina del Conte, Claudio is now counted as a friend of its proprietor, Luigi Pelissero, who is on his knees weeding the vineyard with his granddaughter as we drive up. With great fanfare, he leads us into his shop. There on the wall is an engraving of Camillo Benso, the Count of Cavour, who was Prime Minister of Italy from 1850-61 and the owner of the castle that literally overshadows Pelissero's shop in the town of Grinzane Cavour. "My grandfather started this business," says Pelissero, pointing to the framed property deed, dated 1921. "When the Count died, the new owner was the daughter of his brother, Marchesa Adele Alfieri. She never married. When the Marchesa was 75 years old, she sold everything to private people. She sold the land and left the castle to the commune. My grandfather bought the farm." As we file downstairs to the cantina, situated beneath heavy oak rafters that date back 500 years, I reflect how Grinzane Cavour is one of those towns that embodies Piedmontese wine culture. Not only this 15th century house and its occupant, who carries on the tradition of his grandfather, the Count, and generations of nameless vinters before him. There's also the 12th century castle towering above, where local producers bring their wine every summer for a judging, hoping to earn a spot in its prestigious wine museum and enoteca. (Enoteche regionali are without parallel in the United States. Each district in Italy has one - a combined wine store and tasting room featuring the wine from that region. Many are located in interesting historical sites, and all provide excellent one-stop tasting opportunities.) It's chilly in Pelissero's cellar. He closes his collar, afraid of catching cold, then proceeds to fill our demijohns, sucking the end of a long plastic tube like someone siphoning gas from a car. As the wine begins to flow, he slips a stemmed glass under the stream to catch a sample. "This is Nebbiolo from 1995. It's too cold to be tasted well. It would be better at room temperature," he says, passing me the glass. "With one more year in the oak, this Nebbiolo could become Barolo." Which is to say that Claudio is buying top-notch juice. He opts to purchase some 1997 Dolcetto as well. Still brand new, it will be completely transformed in a year and requires some experience to judge at this stage. Upstairs, as Pelissero fastens the paperwork necessary for transport of wine over the corks, I ask him about the old bottles of Barolo displayed on a shelf. He beams, then recounts a tradition common to Barolo growers. "I have three sons, born 1964, 1966, and 1970," he says, pointing to three bottles with the same dates. Barolo producers set aside 50 to 60 bottles from a harvest the year a child is born, he explains. Then 18 years later, the bottles are available to the child. (Since most Italian wines are drunk young, Barolo is one of the few wines that permits this custom, aging well for 20 years or more.) "This Sunday, my son who was born in 1970 will have a birthday, so we'll open a bottle of 1970. And we do this every two or three years, starting when the son or daughter is 18." What a fine family tradition, I think, wondering how my life would have been different had my parents reared me with quality Barolo. On the other hand, I can't imagine any normal, red-blooded American teenager wanting to spend their birthday with their parents. Here's an even greater cultural divide - but that's another story. On the drive home, I ask Claudio what it's like to grow up in a culture where wine is such an integral part of life. Not surprisingly, some of his earliest memories revolve around the family vineyard his father and uncles tended. It was a tiny plot in Vocemola, a hillside village where his father was born. Claudio remembers the festa after the harvest, as well as his chores - hauling bottles, fetching corks, pressing grapes underfoot. "You don't squeeze the grapes very well with your feet," he acknowledges, "so you did a second pressing with a machine called a torchio. But that was very bad wine, without any body, without good flavor. It was little more than water." The winemaking methods used were centuries old - no cultural fermentation, no steel containers, no aging. "At least it was natural," Claudio says. The culture of analyzing wine - looking, smelling, tasting, comparing - has come to the fore only in Claudio's generation. "For my father, there were two varieties of wine: good wine and bad wine," he laughs. Claudio started learning more about wine from his uncle, who owned a family-style restaurant and took the young boy to purchase wine from the cantine sociali, places where small producers pool their grapes to make wine collectively. At that time, family restaurants generally sold only house wine bought in bulk directly from producers and served in unlabeled bottles, which one ordered by grape type. ("Give me a bottle of your Nebbiolo.") Gradually that has changed. The idea of choosing a wine by producer and vintage ("I'd like your 1990 Aldo Conterno Barolo, please") has infiltrated this casual level of dining, and in the process subtly affected the average Italian's experience of wine. But signs of the old ways are ever present. They're visible in the picturesque wooden wine presses that sit in a family's driveway. They're in the unlabeled bottles of fresh, fruity wine that are still set on your table at a tiny countryside restaurant. And they're in the groin-vaulted cellar of Claudio's 15th century house, which has a vat in the corner for pressing grapes. We haul the wine downstairs and get ready to bottle. I wipe the dust from several dozen empty bottles and rinse their insides with wine. My hands are cold and stained red with the fragrant liquid, which drips through my fingers as I shake and empty each bottle. Some are four decades old, made of thick, weighty glass; others are recycled from last week's meals. Claudio then ciphens the wine from demijohn to bottle using a special pressure-sensitive hose that automatically shuts off when the wine reaches the bottleneck. Soon our garrison is ready for the corking machine - a cast-iron device that resembles a old-fashioned water-pump. Claudio greases its moving parts with olive oil, while I apply a light coating to the corks. One by one, we set a bottle in position, pull the handle, and compress the cork inside a metal iris. A little prong then pushes it into the bottle. And finito. Afterwards, covered with dust and wine stains, we head upstairs to the kitchen. Claudio is carrying a bottle of Barbera from last year's session which he plans to taste for the first time. He's as excited as a child unwrapping a present. A lot of time and energy has been invested in this bottle. Is it worth it? "Yes," he responds. "First, because I save money - up to 50 percent. Second, I want to bottle personally. I like to use my labels, have a cellar with 20 bottles of Barbera from 1995, 1997, and so on, you know? It's like a collection." He sets two glasses on the table. "When someone comes over, you can say, ŒLet's open a Barbara 1995 that I got in the Langhe from Mr. Pelissero. You know, it's very good wine.' You select the wine, you select the corks, you bottle it. You created it - partially - but you did." Pop. A young purple wine fizzes into the glass - the product of a full moon. It's still sharp, but appropriately rustic for two dusty imbibers in overalls. Feeling a sense of accomplishment, we toast the day. Having combined the pleasures of handcraft and harvest, I'm satisfied that I've had a taste of the good life. Patricia Thomson is a regular contributor to PASTA and is president of La Dolce Vita Wine Tours. © 2002 Patricia Thomson |