Keeping up with the Mazzei’s

/As a typical American, I can barely conjure up the names of my great-grandparents. So it’s hard to imagine being Francesco (above)or Filippo Mazzei, who can trace their family tree back to the 1300s. “We’ve owned the Castello di Fonterutoli property since 1435. That’s 24 generations,” says Francesco Mazzei, speaking of the medieval hamlet (below) nestled in the hills of Chianti Classico, which the family inherited 57 years before Christopher Columbus discovered America. The Castello di Fonterutoli winery is now one of Italy’s oldest family-owned firms, run by the two brothers in tandem.

“Actually, a couple of nephews are on the board of directors now, and they always complain, saying, ‘Hey, we’re the 25th generation! Why do you always say it’s 24?’ And I say, ‘Because we’re the boss, and you’re not! When you’re the boss, it will be 25.’ ”

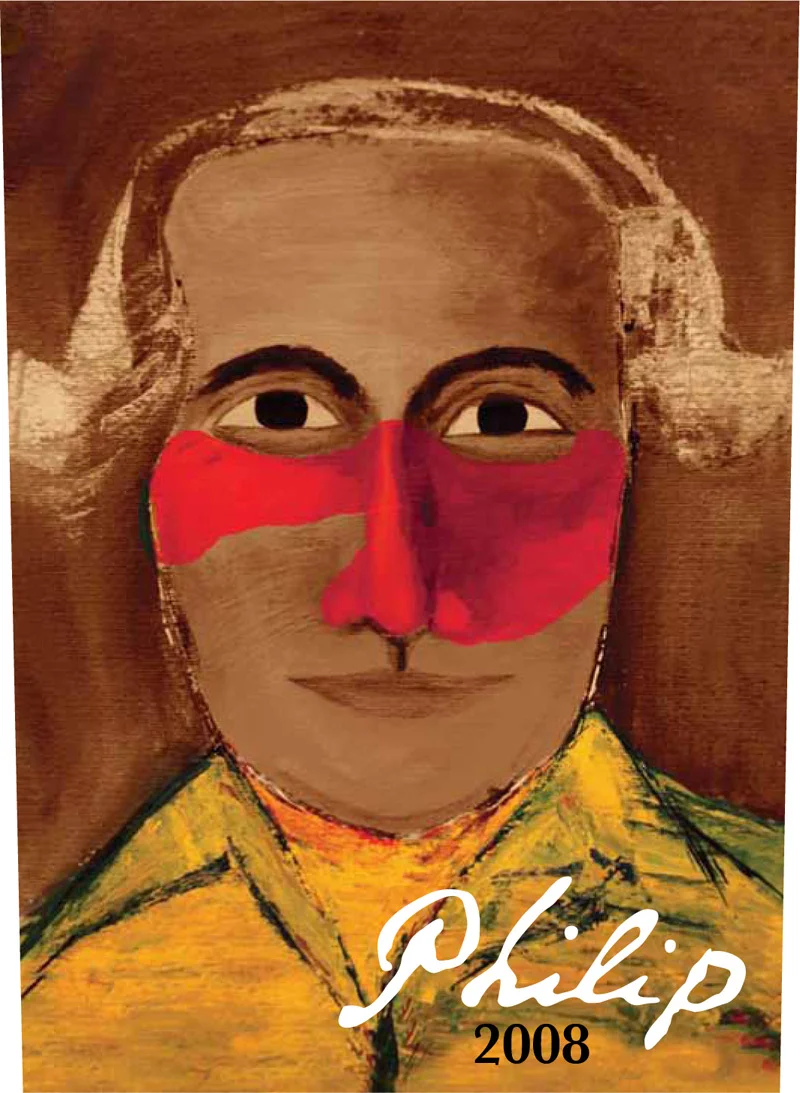

Francesco laughs, then glances at the menu of our lunch spot, settling on roast chicken to accompany the winery’s latest creation, a Tuscan cabernet called Philip. “Please catch a small chicken!” he tells the waiter. Long, lean, and elegant in a light tweed jacket, it’s easy to imagine this CEO powering up the slopes of Mt. Etna on a mountain bike, as he did just two weeks prior to our meeting. The man is fit, with energy to burn.

The modern era of Castello di Fonterutoli began when Francesco and Filippo joined the winery full-time in 1994 and 1989 respectively. Both studied economics and first worked outside the family fold—Filippo in consumer finance, Francesco at Barilla, then Vespa, the icon brands of Italian pasta and motor scooters. “It’s important to manage something where you’re not the boss by blood,” Francesco says.

When the brothers took the reins from their father, Lapo, the winery was at a crossroads. For centuries, it had been a traditional Tuscan farm with mixed crops; wine was just one component.

“You have to think that things changed tremendously after World War II,” says Francesco. “Until then, this kind of farm was managed with the mezzadria—having peasant families who were assigned plots. They had a house, and they had to cultivate that small piece of land.” Sharecroppers, in essence; they kept half their crop and gave the other half to the land owner. “My father was one of the first to change that.” That was in 1955—two decades before Italy officially abolished the mezzadria system in 1974. Lapo Mazzei gave the workers a wage; at the same time, he phased out the farm’s wheat, corn, and other crops. By the 1960s, the property was fully specialized in wine.

For the next two decades, the winery grew slowly but steadily; markets opened up organically. “We saw there was room the push the business ahead. And that’s why we both came on board full-time,” Francesco explains. “We came with the task to grow the business.”

They’ve indeed taken it to a new level. Today Castello di Fonterutoli is among the most revered producers in Tuscany. Producing 800,000 bottles annually, they’re large enough to make several versions of Chianti Classico. Most widely distributed is Fonterutoli Chianti Classico, sourced from the 120 different parcels they own or manage beyond their five main vineyards, with a 10 percent dose of colorino, malvasia nera, and merlot. Though considered a ‘second wine,’ it’s polished, elegant, and always a pleasure. Further up the scale is their chateau wine, Castello Fonterutoli Chianti Classico, coming from 50 select parcels. Now ranked a Gran Selezione (a new category in Italy), this contains indigenous grapes only—sangiovese with a bit of malvasia nera and colorino. Then there’s Ser Lapo Chianti Classico Reserve, made in special years from sangiovese and 10 percent merlot.

Which brings up the matter of names. Several of their wine names hint at significant bits of family history. Ser Lapo Mazzei was a notable ancestor who served as notary to the Tuscan merchant Francesco Datini in the 1300s. A meticulous record-keeper, Datini amassed a voluminous correspondence that has survived intact. (This formed the basis of Tim Parks’ excellent nonfiction book TheMerchant of Prato.)

“He was the first to introduce the letter of credit,” Francesco says of Datini. “So he was the first dealing with all of Europe, not paying cash, but paying with letters written by his notary.” Among those papers is the first documented reference to Chianti as a wine, written in 1398: “In one of these letters, Ser Lapo writes that Datini is buying a few barrels of Chianti wine from another guy. The funny thing is, the wine was from Chianti, but it was white! But at that time, Chianti was a little bit of both.”

A more recent ancestor gave his name to their latest wine: Philip Mazzei (above, in a Louvres portrait by Jacques-Louis David), a cabernet sourced from their two Tuscan estates, Castello di Fonterutoli in Chianti and Belguardo on the coast. This 18th century forbearer was a friend of Thomas Jefferson and planted the first vitus vinifera in Virginia. (Read more about Philip the man and Philip the wine in my article “Meet Philip,” in the February 2015 issue of Tastes of Italia.)

Mix36 gives a nod to the family’s more recent enterprise involving clonal research on sangiovese, an ancient grape prone to genetic mutation. This wine is a blend of 36 sangiovese clones and biotypes. The difference in terminology is a matter of whether or not they’ve been officially cleaned of viruses, certified, given a code name, and commercialized. There are dozens of sangiovese clones that have gone through this process, but probably hundreds of biotypes in Tuscany and neighboring Emilia Romagna. Many were studied during the Chianti 2000project, a massive joint research effort overseen by the Chianti Classico Consortium. “It was started when my father was chairman of the Consorzio,” says Francesco. “He was the leader of that job—which is one of the biggest investments made for clonal research in the world.” Castello di Fonterutoli also devoted some of its land to the experimental vineyards during that time.

“What we have at the estate is 18 certified clones that you can buy at any nursery. Another 18 sangioveses biotypes are proprietary with us,” says Francesco. “They’ve been propagated from our old vines, and you cannot buy them.” All go into Mix36.

Which means is that Mix36 is wholly unique: Not only does it contain historic sangiovese biotypes that no one else has; what’s more, it can simultaneously be called a blend, a monovarietal, and, coming from one vineyard, a cru. But it’s also very much au courant, typifying the trend nowadays in Tuscany to blend sangiovese types—getting a hint of violet aroma from one, more tannin from another, and so on.

The team behind the blending is Fonterutoli’s agronomist, their enologist, and the famed Tuscan consulting enologist Carlo Ferrini. Francesco and Filippo join in during the penultimate step. “At the start, you go into the room and there’s a big table full of bottles. It’s incredible. “You need to be very talented,” he says. “I know where to end, but I wouldn’t know where to start.”

Be that as it may, Francesco and Filippo Mazzei have ushered an entire winery to fruition. And that takes talent too.